August, 1960: an unbearable day—the temperature well over a hundred degrees on the concrete runway at Dallas Love Field where I am pitching bags off a conveyor belt onto a luggage cart, unloading one of the Vickers Viscount aircraft that Continental Airlines flew in those days. Next to me a mechanic jokes with a coworker as he takes a wad of chewing gum out of his mouth and stuffs it into the guts of a turboprop engine he’d been having trouble with. “That ought to get ‘er to Albuquerque!” he opines.

True story. I have no idea what happened to that airplane, though I certainly hope it got to Albuquerque safely. I should probably have reported that mechanic to somebody, my boss maybe—but I was too frazzled and tired and drenched with sweat (besides being too low in the pecking order) to think that. I’m a bit ashamed that I didn’t report him, though not as ashamed as I ought to be, and I soothe my conscience with the absence from my memory of any stories of plane crashes from around that time.

Thirty years later I published an essay entitled “The Ultimate West.” It has several weaknesses, the chief of which is an excessive literariness, to which I am still prone. I’m not ashamed of it though, and I’m thinking of a particular paragraph I wrote then about childhood trips to Albuquerque from Abilene, Texas: when my mother would put my brother and me in our 1939 De Soto and drive us there in one day. It still seems remarkable to me that she did that. We would usually stop in Clovis for lunch, which consisted of roast beef sandwiches at a restaurant in a small downtown hotel. I remember parking meters and brick streets in Clovis, but another memory, another kind of memory predominates.

Getting to Albuquerque was for me the most powerful of symbols. Texas was plain, New Mexico exotic and cosmopolitan. In Albuquerque I went to school with Mexicans and an occasional Indian, whereas my Texas schools protected my Scotch Irish ethnicity against cultural pollution and forced me to memorize Bible verses, which I still think of as Baptist, at school.

I did a lot of growing up in Abilene. It had been my mother’s family home since 1926, the place where she and my father met, fell in love, and married. We lived in Abilene with my grandparents during the early years of World War II when my father was in the Philippines. We moved there more or less permanently in 1948 after his death had been confirmed. But both my brother and I had been born in Albuquerque, I in 1937 and he in 1940. We both started school there; though I had a longer exposure to school in Albuquerque than he did, from first through fourth grade. The road trips I recalled in my 1990 essay took place between 1943 when we moved back to Albuquerque from Abilene and occupied the house my parents had built on Tulane Place near the university, and January, 1948 when we resettled in Abilene.

And of course there were as many road trips to Abilene as to Albuquerque in my childhood—but although I have many cherished memories of visiting and living in Abilene as a small child and continue to love my adopted home town, it is the road trips to Albuquerque that my memory assigns to a special place among my magic things. “I could feel my heart rise in me as we passed the state line at Farwell and it mysteriously got an hour earlier.” Not even the seemingly endless succession of wolf and coyote skins strung on the barbed wire fences along the roadways dampened my enthusiasm. But in spite of the fact that Albuquerque gave me a childhood sense of something like cultural diversity, what I didn’t understand as a child was that both in Northern New Mexico and in West Texas I was living in places where perhaps a hundred fifty years of history had been erased. It is my connections with that history that I continue to ponder and with which I still strive to come to terms.

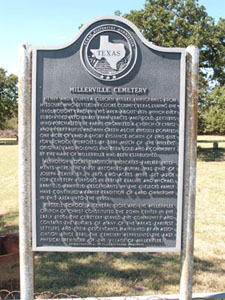

Last fall, on my way to my annual high school class reunion, I made another road trip, in a rented car, to the Texas ghost towns of Duffau and Millerville, not far from the present day town of Hico, on the edge of the Texas hill country. I made the trip to search for my great grandmother’s grave. She is buried in Millerville Cemetery, according to her death certificate. I didn’t find her grave, but I suspect it may be one of a good many graves in the old cemetery that are marked with field stones bearing no inscriptions, or that it may never have been marked at all. Her name had been Melinda Ava Akers. She was born in 1843 in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, and had moved with her extended family to Bloomington, Illinois, some time before 1870. She was just shy of seventy years old at the time of her death in 1913. Her journey from Pennsylvania to Texas had been long and meandering.

My great grandfather, John H. Long, outlived Melinda by twenty-five years, married again, and died in Los Angeles, California in 1937. I should like to know more about him and my great grandmother and his second wife, one Mary Floyd Marcoux, though I now know a good deal more than I ever did growing up, when I don’t think I ever heard their names. Apparently, my great grandmother’s death certificate mentions only one child, her daughter Marian. But Marian was the youngest of four siblings, two of whom, Florence and Raymond, are buried in New Florence, Missouri, and one of whom, James Olin, was my grandfather. Here is a photo of John Long, for which I am grateful to my cousin, Carol Flanagan. I have no idea where it was taken or when, though the subject looks to be middle aged. I’ve not been able to find a photograph of my great grandmother. John Long was six years younger than Melinda Akers when they were married in 1876. I have no idea how they met or where, though I have traced John Long to his birth in Peoria County, Illinois, not far from Bloomington. He and Melinda show up together with their then two children, Florence and James Olin, in the United States Census of 1880 in Minneapolis. Their southwards migration through towns in Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri (where they lost their two children, Florence and Raymond), would bring them to Beckham County, Oklahoma, some time prior to 1905 when my grandfather, James Olin, and Adda Belle Peterson were married at Guthrie.

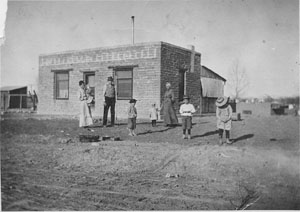

I knew none of this growing up, perhaps because we lost contact with my father’s family after World War II. For a long time Grandma Long would come to visit every few months, but finally the visits stopped when she moved to Hawaii for a while—she too was a wanderer. The extended family of Longs and Petersons lived in Oklahoma until 1911 but seem to have split up after that, with John and Melinda and their daughter Marian, who had married a man named Orlando Curtis, going to Texas, and my grandparents and Melissa Peterson settling finally in Las Cruces, New Mexico. Here’s a photo of the Las Cruces clan, I think from 1913; Peter Peterson, my maternal great grandfather who had died in Oklahoma in 1910, is absent. My grandmother is holding my Uncle Bill, the baby of the family. My father is the boy in the middle between my grandfather and great grandmother Melissa Peterson who is holding my Aunt Frances’s hand. Next comes my uncle Randolph and finally, a neighbor boy whose hat covers his face. I never knew my grandfather, James Olin, who died in the flu epidemic of 1919, but I spent a number of happy childhood times at the Las Cruces farm—we didn’t call it a homestead, and of course I’m remembering it as it may have been thirty years after this photo was taken. I chiefly remember sleeping on a screened-in porch on cool summer nights and waking every so often as a train hooted by on the tracks close by. My memory is that the porch faced the railroad, though that could be wrong. I also remember the farm as a garden. Grandma Long kept bees and dairy cattle in addition to chickens. She raised vegetables and I don’t know what else. There was a lot of alfalfa grown in that part of the world in those days. I associate the smell of alfalfa with Grandma Long’s farm and find that smell exhilarating still.

Here’s a photo of the Las Cruces clan, I think from 1913; Peter Peterson, my maternal great grandfather who had died in Oklahoma in 1910, is absent. My grandmother is holding my Uncle Bill, the baby of the family. My father is the boy in the middle between my grandfather and great grandmother Melissa Peterson who is holding my Aunt Frances’s hand. Next comes my uncle Randolph and finally, a neighbor boy whose hat covers his face. I never knew my grandfather, James Olin, who died in the flu epidemic of 1919, but I spent a number of happy childhood times at the Las Cruces farm—we didn’t call it a homestead, and of course I’m remembering it as it may have been thirty years after this photo was taken. I chiefly remember sleeping on a screened-in porch on cool summer nights and waking every so often as a train hooted by on the tracks close by. My memory is that the porch faced the railroad, though that could be wrong. I also remember the farm as a garden. Grandma Long kept bees and dairy cattle in addition to chickens. She raised vegetables and I don’t know what else. There was a lot of alfalfa grown in that part of the world in those days. I associate the smell of alfalfa with Grandma Long’s farm and find that smell exhilarating still.

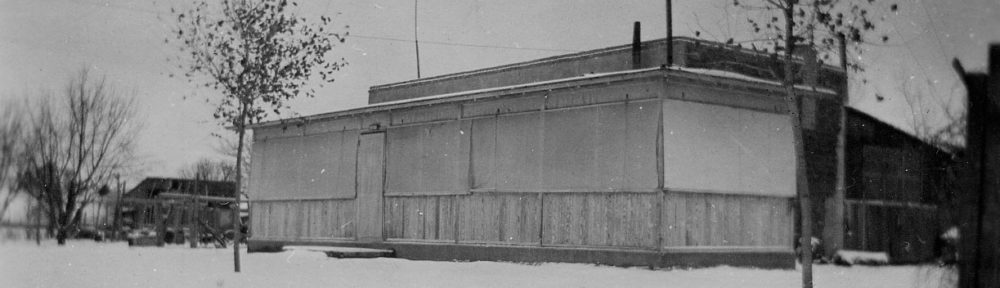

And I think that farm was a sustainable enterprise as long as Las Cruces remained rural and as long as climate cycles allowed. Of course, all the farms in that place were irrigated. The irrigation ditch that brought water to them from the Rio Grande was the chief feature of downtown Las Cruces in those days. My mother once told me that my father and a friend wrote a book about what she called ditchwater Spanish, which my father spoke fluently she said. That expression, ditchwater Spanish, suggests to me that my father and other boys, not all of them Anglo, must have played in and around that irrigation ditch much as I and my friends sneaked away and played in the dry creeks of Abilene. I have the address of the Las Cruces farm but think it exists no more. A 1998 photo shows only the railroad right of way. I’ll go to Las Cruces and look for it one of these days. My favorite of the handful of photos I have of the place is one I’ve used before, because it shows my grandmother and her four grown children. I should say too that I am grateful for all my photos of the Long Homestead to my cousin, Lorian Choate, and her husband, Brett Martin. Another I love just for the way it shows the house, is this winter picture.

But central to the lives of all of us who gathered from time to time at that farmhouse was the fact that we were inheritors of what we now sometimes call Indian removal. We were the first couple of generations of Americans who profited directly from that experiment in ethnic cleansing. But we didn’t think of our lives that way, and part of the reason we didn’t was that history had been cleansed for us as well, in Texas by the banishment of everything native American including the people, and in New Mexico by commodification. Our story, the story of our times and our places in them, was a story of migration into a place that had been empty of human culture before our arrival, or so we thought. Our stories of heroic journeying, cowboying, and the like, neglected to mention the people who had been there before us as human agents engaged in civilized life.

To be continued . . .

Thanks Julian, great story.

Thank you for sharing. I love Northern New Mexico and seeing it through your eyes makes it even better.

A fascinating read. I have in my possession a scrap of paper composed by my grandfather as he lay dying of cancer in 1943. In it, he says he came to west Texas in 1876 in an “ox wagon” with his family, from Logan County, Illinois. I have his wallet, and also his ration card. There are stories of my great-grandfather and -grandmother–a Franklin and erstwhile aristocrat–meeting in Tennessee during the war, while she hid with her family hid under what was left of their Big House, and passing northern troops pursued, but failed to catch, the single pig that was all the food they had. She went into the woods, and instead of finding the pig found my granfather Clay, who evidently was selling supplies to both armies, and was said to have a wagonful at the time. Some sort of arrangement was made, I gather, and they survived and were wed. Priceless stuff. Thank you, Julian.

Thanks, Kevin. Good story about your grandparents. I’ve also enjoyed your Blank Sonnets. Are they together somewhere where I could read through them all without scrolling through your old Facebook posts? I’m going to keep going with the memoir but break it up here and there to rant about other things. A package arrived a couple of days ago from a cousin with some keepsakes of my Grandma Long’s. Among them are two very old letters, one from a sister-in-law of my great grandmother’s and another from my great grandmother, herself. this is the great grandmother who died in Hico. Both letters were written to my grandparents. I’ll be talking about those letters in my next post, I think. Great to hear from you!