Electronic publications:

“Bryan’s Ragtime Stride” Friends of Scott Joplin, January 13, 2020.

“Nineteenth” The PIker Press, June 14, 2021.

“Farm Road Entropy” The Piker Press July 19, 2021

“Deep Ecology” Better Than Starbucks, August 2021*

“Mnemonic” Eunoia Review, August 4, 2021.

“Great River Road” Eunoia Review, August 5, 2021.

“West” Eunoia Review, August 5, 2021.

“Zapper” The Piker Press, August 16, 2021.

“Poem in August” The New Verse News, August 30, 2021.

“Colloquy With Dean Rader and Emily . . . .” Litbreak Magazine, September 18, 2021

“Events of !939” Litbreak Magazine, September 18, 2021

“Nomad Country” Litbreak Magazine, September 18, 2021

“Lament for the Makers” Litbreak Magazine, September 18, 2021

“After Implosion” The Piker Press, September 20, 2021

“End of the World” The Piker Press, October 18, 2021

“Pandemics, So Called” The New Verse News, November 8, 2021.

“Anthropocene” The Piker Press, November 15, 2021

“Duncan and Brady” The New Verse News, November 19, 2021; reprinted in CulturMag, December 1, 2021.

“Springtime 2019” The Piker Press, December 13, 2021

“Long Homestead in Winter,” The Piker Press, January 17, 2022. Reprints in O’Henry and Pinestraw.

“Three Eco Reflection Poems” Lothlorien Poetry Journal, January 30, 2022.

“The Alpine,” The Piker Press, February 14, 2022

“Bayboro Harbor 1999” Raw Art Review,SUMMER/FALL, 2021, pp. 129-130

“Silverback” The Piker Press, March 21, 2022

“Chain of Rocks”The Piker Press, April 18, 2022

“Pure Onionhood”The Piker Press, June 27, 2022

“27 Club”The Piker Press July 25, 2022

“Field of Dreams, 2022” New Verse News, August 14, 2022

“Greek to Us” The Piker Press, August 29, 2022

“Wind in the Willow” The Piker Press, September 26, 2922

“Moonshadow” The Piker Press, October 24, 2022.

“Searching for Amédé” The Piker Press, November 21, 2022.

“Penguin Provender” The Piker Press, December 19, 2022.

“Recuerdo” New Verse News, December 23, 2022.

Johann’s Boy The Piker Press, January 9, 2022.

“Winter Cyclone Haiku,” “Johann’s Boy” Verse Virtual, February 2023.

“Oil Patch, 1980” The Piker Press, February 27, 2023.

“Against Melancholy” The Piker Press, March 27, 2023.

“Animal Counsel” The Piker Press, April 24, 2023.

“May Day” The Piker Press, May 8, 2023.

“Earthrise” The Piker Press, June 19, 2023.

“Almost Ghazal for Them Cowbirds” The Piker Press, July 17, 2023.

“Microaggressions” The Piker Press, August 21, 2023.

“In the Name of Heaven” The Piker Press, September 25, 2023.

“Towards an Unaesthetic” The Piker Press, October 23, 2023.

“More than Macaronic” The Piker Press, November 20, 2023.

“Epiphany at the St. Louis Art Museum” The Piker Press, December 18, 2023.

*featured poem

Watch this space for forthcoming electronic publications.

Selected Print Publications

“I have heard of this book already,” said Don Quixote, “and verily and on my conscience I thought it had been by this time burned to ashes as useless . . . .”

*High Wire Man . . .

High Wire Man · To a Woman, Singing · Under Construction · In Durham, Living on the Margin · Wittgenstein’s Lion · Fuþark · Homunculus · Philosopher · Murder Sonata · Vocalise · No Thanks · Bach’s Retraction · Symposium · Take the Hard Road Home · Heart of Flight

*Trilobite Press has been sold to Triangle Nonprofit Publishing, whose website is a work in progress. If you’d like a copy of High Wire Man, write here, or write the author at longjulian@gmail.com.

“These . . . ,” said the priest, “do not deserve to be burned like the others . . . , being intellectual books that can hurt no one.”

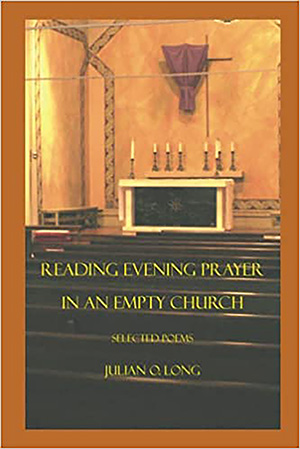

Reading Evening Prayer in an Empty Church . . .

This collection includes 80 poems. Here are some selections. American Pie · Autumn Catalogue · Train to Dallas · Reading Evening Prayer in an Empty Church · Flatbush Waltz · The Echoing Green · Obiter Dictum · Pressmen · Salvationists Escaping · From a Further Room · Christmas Eve · Streams of Mercy · In sure and Certain Hope · Weymouth Woods · Monumental History

This collection includes 80 poems. Here are some selections. American Pie · Autumn Catalogue · Train to Dallas · Reading Evening Prayer in an Empty Church · Flatbush Waltz · The Echoing Green · Obiter Dictum · Pressmen · Salvationists Escaping · From a Further Room · Christmas Eve · Streams of Mercy · In sure and Certain Hope · Weymouth Woods · Monumental History

American Pie

Janis Joplin was a tough

little Texas girl, you said

who busted her butt to be a star

but if there was ever any music it disappeared.

Maybe we never heard it anyway.

If there was ever any music

I lost it at the Eagle cafe

where lunch was Theresa Brewer

and my friend Jack Benny Cunningham’s yellow boot

came down on the neck of a little Mexican

we’d called a wetback–

we could have killed him.

The week before, we’d killed a deer

trapped him in the headlights, bird-dogging

in my granddaddy’s old Dodge. Then we were

on him with pocketknives, and the more he

struggled the more we cut, until

he stopped.

But I think Janis Joplin died of hype

and when the music disappeared behind

night-slapping windshields from Newark to Saigon

we didn’t understand. All we ever wanted

was to get there.

Have you outstripped the rest?

Are you the President?

Out on the road

You’ve got nothing left to lose, born again

and amplified, faster than Richard Petty

drop-kicked through the goal posts of life.

[First published in New Texas 1998, 1999]

Autumn Catalogue

Bravely

as the light flies

I tell you how my heart breaks

for one red maple

on a hill in South Carolina

and for a redtail hawk

how autumn tramped that country

in dirt feet, keening

like an old song. I reason

that things are most themselves

in autumn when at four o’clock

the sun from high cirrus cuts

tall poplars.

Their yellow hands holding the blades

they abide the time

over farms

and country roads. My hand

translucent as I

write by this window

displays its architectonic–

tendons slide along the knuckles

gently lift the net of veins

where the life goes home, and I recall

how soft your eyes are sometimes. If

my character likewise

should be exposed

it would be found a somewhat overbloomed

perpetual. But if found at best

I think I could hollow out my bones

wait with the redtail hawk

in a known spiral upwards, all

utterance suspended. Glaciers snap

quite suddenly

my hair is white, a hawk cries

westward.

[First published in Weymouth:An Anthology of Poetry Edited by Sam Ragan, 1987]

Train to Dallas

As I have moralized it

we rode through grey

December pastures

half-steamed windows

of our coach revealed

black against them here and there

mesquite, post oak, scrub cedar. I

nodding into Lear, as Kent

into wheels turning, kept the

season in the stocks.

Dead father, please come back!

I, too, would lead you by the hand–

Look there! cried the old mad king

closing Cordelia’s eye, a door

to tombs in Leicester whence he went

that day the rails beneath me throbbed

as though they were the joists of heaven.

There is a grief of old men, saturnine

as Texas winter towards the solstice–

my grief too, borne inward as the death of God.

The oldest have borne most, been comfortless

incapable; my grief to search for fathers I had wronged

by too much love.

[First published in Pembroke Magazine 1978]

Reading Evening Prayer in an Empty Church

It’s good to be here, Lord,

even if you’re not, even if all

that’s behind the crucifix

is the eastern wall.

Chrysostom says it takes two.

I’m never sure that angel on the back bench

knows anything, sitting there with his big square

wings folded, reading the editorials.

I’ve seen his kind streak across the sky

now and again, bound for races or baseball,

thrown a few high thoughts their way,

but I don’t really want their life.

Not that here is an easy place.

My clothes are too tight. I worry. Sometimes

I get depressed. But what if I stopped

in this place just to get my messages?

This here, this room into which I speak

is quite enough height for me, and maybe

someday we’ll all of us get the message. Home,

this is home, with its not very permanent light.

Here or nowhere, me or nobody–

it’s well.

[First published in Windhover, January 2001]

Flatbush Waltz

In a book he called Thad Stem’s First Reader, the author recalls his first love, a young woman named Rose Blatz, who taught him a few words of Yiddish, and whom he characterizes fondly as the ninth candle of the Hanukkah menorah. Of the ninth candle, Leo Rosten observes that it stands taller than the rest, being the candle from which the other eight candles are lit, one for each day of the feast, and symbolizing that one can give love and light to others without losing any of one’s own radiance. Jessica is Shakespeare’s Jessica, in The Merchant of Venice, who might have had Andy Statman’s Flatbush Waltz in mind, when she said, “I am never merry when I hear sweet music . . .

[In a doggerel rhythm, like a slow waltz]

Kings and queens in their limousines,

like these in their threadbare velveteens

were pearls that we stitched da da dum

da da dum

and now our dance is plain as boards

but our feet still turn as we sway, da da dum

we are sober as sawdust, flat as shirts

but we flame as we step, we shine, da da dum.

Dum da da dum two three dum each tink

of the mandolin drums to the fiddler’s tune

curling and sad and sweet da da dum

like Hanukkah candles or wine from a spoon.

When in sweeps Jessica nee Rose Blatz

ninth of the candles, or first, da da dum,

she shines in full measure, out-darking the time,

the fiddle bow stitching up skeins of pearls

to the music she steps, da da dum da da dum.

Come along you squires, you easy riders

madonnas with chutzpah and pizzazz,

put an ear to the witness, eye to the shine,

put your foot, mark the music, it droppeth

like rain.

This sad sweet waltz is a journey somewhere–

beyond some long march, out past the last prayer,

the last mitzvah waiteth with Jessica there.

Dance is commanded, no wallflowers here,

they shall dance in Jerusalem all, next year.

[First published in Windhover, January 2001]

The Echoing Green

As many times upon the running lawn,

The spangled night of iris-fragrant spring

Was the various and populated town

Of our first knowledge of near everything.

No tigers prowled about in that first world,

No spiders in the fragrant lotus there;

Around our rose-tree house a serpent curled

Benign and fructed sleeper, centered fair.

We played creation round about its head

Magicked friendship from the tuneful skies

And being spectral, chaos shrank and fled

Finding the darkness deep as we were wise.

Now, having lost the mothering gift of play

We strain at common love the livelong day.

[First published in The Sewanee Review, Spring 1972]

Obiter dictum

It was five a. m., the papers say

when you slipped away in your sleep.

It must have been a quiet departure

unlike you, who were seldom at a loss for

words. I’m damn sorry I missed your funeral,

sorrier to have missed your conversation

all these years.

Not that you were unquiet–

you held it in and wept, if you wept,

in a place apart (not unlike the rest of us either

wearing charity like a millstone). I often found

you behind your old Underwood at the paper

banging away with two fingers at that old devil

language. I learned from you never to use the

word rue or to put a comma at the end of a line,

learned to value some common truths, like the

way you always asked, “How you feelin’?”

and probably meant it. I miss you no more

today than during ten years silence

though the thought of you grows hollow.

You were a sociable man. I found it

easy to love you

and knew you loved me because I knew you to hate me

once. I had seen a weakness you couldn’t abide–

the circumstance no longer matters, but the truth

can’t be left out. Like the memory of torn pride

whatever we carry of others in us,

stays.

[First published in New Texas 1998, January 1999]

Pressmen

It is late. I sit at a long deal table

in an upstairs cafe across from the paper

and watch the pressmen come in from their shift.

We will drink coffee for a while. Again I will think

I know why they wear those squat little hats

folded from newsprint, why they do not

take them off–then we will go.

The hats are a disguise to make themselves

pressmen, like gunnery sergeants or stevedores–

a disguise and a badge. “We are men,” they say,

“who tend a machine, feet sunk in fifty-foot rock

and long as a football field, that rips words from air

as it whirrs like a saw, eats ink, tree trunks, arms.”

Most have fingers missing, some have more.

One tips back his chair and tells a story about his son,

pushes the hat back on his balding head and scratches;

another tips the hat forward, tells of an argument

with his wife, as if to say, “You know how women are.”

Here, at the end of their shift, they still need to wear the hats–

even as they wrap the arms of their minds around each other,

because they are men with stories they do not

entirely wish to tell.

And that is because they aren’t really pressmen at all.

One is a breaker of horses, who carries a fire in his belly

that drives him to make subjects of hammers, automobiles,

his lawn mower. Another is drunk on God. In the dark

hours away from the press, God visits him. They smoke

a calumet together, tell lies and love the lies they tell

as though they were incense drifting up from sacrifice.

The central one, he to whom others defer, will one day be buried

with his weapons. When centuries lift the broadsword from his ribs,

they will find him to have stood seven feet tall. And the small

one at the fringe of the group, the dark one who smiles a lot–

no one knows he loves a woman who sang to him once in Greek.

A luthier, he sleeps in the grain of true and high harmonics

a sheet of spruce thin as a plectrum crushed to his ear.

[First published in Windhover January 2001]

Salvationists Escaping

The crisis is always the same.

What if, after collecting coats and toys

TV sets, gratuitous old shoes, we should slip

broke and walking out of Sherman’s Atlanta

barely ahead of gangrenous caissons and burning?

And suppose the children were not

the same every year with surprised grandmothers

getting canned goods and hand me downs, but refugees

with swollen bellies begging the roadside

and sooty fingers plucking our penniless sleeves.

It has somehow to start elsewhere.

The world I make love to has always

had your skin. Its roots and contours

swim in your sea, telling each other touching

all the things that are told.

Yet there is always that other, sometimes

so much of it we die for a while or a lifetime

(once as a child I caught the same

tiny fish forty-seven times). In Sherman’s fires

we swim, tiny fish in buffalo grass.

Love because you must before the world wakes

to the dead city and everything gone but smoke.

Tug at each other’s coatsleeves. Do not let go–

as though there were someone to forgive the burning

as though there were someone to love us but ourselves.

[First published in New North Carolina Poetry, The Eighties, Edited by Stephen E. Smith, 1982]

From a Further Room

—for Dona and Rob Anderson

“But is it really

music?” you complained.

We were talking of Stan Rogers, coming out

with new tunes even though he’s dead, music

(or not) mostly made at the engineer’s board.

I thought of dour old Mennonite women

on hand at the fair in Iowa City

like my Swedish grandmother, long since moved away.

New music made them stiff last year. ‘I’m here,

but I don’t like it,’ their demeanor seemed to say.

New gospel, slick as TV, gave them nothing to pat their

feet to.

Earlier, we had talked of your new house in Door County,

seen photos of friends on a friendly beach. Rob mused, “We

wrote three books together,” pointing out one of them. Then

we talked some more about land and trees and water,

I still thinking of “Paradise” and saying

fretfully how we blow whole mountains away

and think to make it good by planting grass.

If new music fails perhaps it lacks something

of the earth we know. Gordon Bok sings of weather

I can only imagine, being southern; yet his voice, recorded

fills a room, sonorous as woodsmoke. Listening, I almost think

I’ll be a Maine man too. Rogers, doubly absent, sings of Nova Scotia

—but the rhythm is a Texas two-step.

So if music pegs us to known earth, maybe new music

reminds us how we are sometimes tied to objects of desire

we don’t understand. A damsel with a dulcimer

in a vision once I saw . . . heard melodies are sweet,

but those unheard are sweeter, as once in Taos

I watched a young woman dance alone

in herself, complete—

taking, as she did, space meant for a hundred.

New music surprises us, arrives all at once in the air

from nowhere we had ever expected to go. Sometimes

we don’t like it, but this year the Mennonites rocked

to the strains of “I’ll Fly Away”—

and perhaps all music is new,

like sleep on the westbound porch

at my Swedish grandmother’s house in Las Cruces

where the Santa Fe whistled hollow and high.

Nuzzled as close to some heart of it as we can get,

we sometimes write books, cook risotto, argue—

take naps in the moonlight while somebody

not present calls the tune.

[First published as a broadside by Backroom Window Press, 2011]

High Wire Man

He starts at dawn.

From a hill above a tiny

French village a wire stretches up

over cottages parti-colored, harlequinesque

a single steeple, tall beeches swaying.

He walks at first like a tumbler, leaping

and changing his feet, turning cartwheels

about the pole that balances–one false turn

but he catches himself last instant before

dead weight–and then the long stride

over the housetops, each step centered

afresh.

Do we really hope he falls–

Isn’t it the overcoming that thrills

each step an overcoming not of death

but of something like slavery, on the wire

to fail beyond shame? We imagine fear of

broken bones and agony, death of deaths

by violence, but ask him and he’ll tell you

he is at home on the wire. Think of the pole

the balancing, the purity of it. Any life

he loses isn’t his own.

From his heart stretches another wire

tugging towards the hard planet–

what he risks is loss of height, but in

the end the heart implodes, wires run to ground

over a little stile, step foot in a field of folk.

We cheer and weep–ask and he’ll tell you

he was at home on the wire.

Under Construction

–at the MoMA in 1983

What did Rilke mean

«you must change your life»

that a dead god speaks

through a broken statue?

or that the statue, mutilated, is

the god, absences noted–

here in the MoMA the issue is

simpler, most of the galleries closed.

A rope separates me from The Starry Night

whose “careful use of line, space, and spiral

. . . creates a sense of reckless speed.” It is

nonetheless a small canvas. The cypress

in the foreground enflames less than

observes, a lonely spectator almost outside

the rope with me. Van Gogh needed a wall.

Nearby trois demoiselles, huge and histrionic

scandalize the room, its neutrality, its spotless

temporariness. The heavy brushstrokes of their thighs

are brass fists–the flat planes of their faces slap the air.

What absence teases here? Art deco furniture

Bauhaus models, an Escher drawing or two

return to book–Van Gogh returns to book.

Only the bawdy demoiselles disturb the silence.

I turn to them, smug as if

to say: Be still! We are in charge–

see, we have shouted these others down

and nothing will ever be the same.

Wittgenstein’s Lion

Wittgenstein . . . made the most interesting

mistake about animals I have ever come across.

At the end of the Philosophical Investigations he

says that if a lion could talk we wouldn’t be able

to understand him.

—Vicki Hearne

If some lion were to speak

(to say nothing of lions at large)

that one would be a failed beast

thin-maned and ugly, lacking among its kind

any familial tie to the king of

same.

A hearer of voices, that

one would scheme of poetry–

in the desert would invent

riddles that slouched like athletes

thick muscled, gigantic.

Of course, the lionist culture would fail

its pretensions exposed by a skinny Algerian.

A postcard mailed from a desert town

requesting copyright, would be returned

because it arrived without a stamp

but think of the romp they would have.

Lionish translations would burgeon–

Imagine the Nicomachean Ethics roared

the Iliad’s great periods hugely purred

the New Testament conceived

as an antelope hunt.

Soon would arise a tradition

of lionist conversation, courtesy having

its Leoniglione, politics its Leonavelli

verse a Leonighieri, a dolce stile

a sprezzatura of the leonine.

In the new lionist Aeneid

the hero remains in Carthage

to wed the African queen.

Having conquered the interior

the lovers found instead of Rome

a belletrist academy

teaching all subsequent history

to keep a civil tongue.

I made nothing–

that has to be said

at first, not the little

klavierstücke so loved by parents

(hated by children) not a cantata

toccata, passion, chaconne,

not the great fugue, none of it

I made.

Nor, and this is hard,

was I its instrument–not one breath

in the pipes that caused these hands

and feet to dance on burnished wood

was mine. I felt that breath,

thought it, I suppose, like Pascal’s

reed, knew it even for what it was

«soli deo gloria» but I never . . .

better to say, my God,

that it made me.

And the great fugue?

I laid it out, signed it, sought

to perfect it, failed; but the heart

of it, peace to men of good will–

good will the highest good of all

sublime above all other–some profess

they were taught it by a philosopher;

I forget his name, a pietist I think,

no matter. That was the great

fugue, not mine but God’s.

Had I been its instrument

I should have died sooner, incarnate

lost in its incarnation, surviving

only as long as memory lasts;

but we know that God’s music (there

is the word) sheds its skin like cicadas

I used to find as a youngster in Eisenach

choristers whose thousand juicy voices

thronged high summer nights. Nor was

the what the wonder, more nearly the whence–

brilliance of silence unfolding with jeweled speech

(don’t believe the philosophers, music is sound)

and oh my Lord my God the rush of it, sometimes

not to be borne, the organ bench my only safety,

only calm in the wind that made me crazy!

The muse first sought me out in the church

at Arnstadt; we made music weekdays

until the council discovered us.

An angelic flute she was, in the antique

style, God’s voice a violone,

wheeling like the planets–I had been

to Lübeck to hear Buxtehude play

overstayed my time, neglected my choir . . .

I’m no good for philosophy. Give me black

and white keys, wood diapason, reed diapason,

gut, tin, or brass, handy, homely things: I am homesick–

always was homesick–the great fugue

took me home.

Twelve o’clock we keep the feast.

Like promise of familiar grief

the time surrounds

as carols pour from deepest flutes

for which there are no organs and

the solemn plainsong is as light

suffused in darkness of the one

beginning.

A boy steps to the pulpit,

the antique ruff at his neck

the type of an antique tongue.

He reads by candlelight an antique tale

of a maiden in a garden and a star.

As the miracle is announced in his choirboy

Voice, piped in this house to which both it

and he belong—there

is the breath of God.

We should do well to ask

him where the story

begins. He cannot tell us

but we may discover the child

beneath the altar, find in memory

of him or her joy glimpsed down corridors

not closed, merely unopened until now

here in the darkened church

hung with rosemary.

We do not speak of the one beginning

carrying it within as though we stood

at daybreak by the sea, naming

as we did when we were small

creation’s names, thinking to relearn

languages of birds, fish, grasses

of stars and their spectacular companions

in the long and open night, now lost

with the designs of our first parents.

I dream an archaic woman

offers her man child to a star

that it inhabit him, become

his heart, burn fiercely as he burns in life.

Later, he will learn the song one sings

to the great eland in the three-day hunt

running sometimes two hundred miles

across the desert, learn the ticking

in his chest that is the eland’s reply

and finally the prayer one offers

to the spirit of one’s animal friend

(a person of the early race),

whom one has killed and eaten

as one must, begging his pardon

as one must. I cannot myself imagine

the speech of elands or a lived experience

for which to converse with beasts

is an ordinary occupation

not reserved for saints or children,

or affect to know the end

or seek beginnings in observances,

dramatic gestures, when to search

there is ever and again to find

darkness at the edge of flame

last ripple either side of birthdays

coming and going, always in time.

Limited by my skin, I must

be just here, discontinuous

with all I seek to know. We have come

into this place and said the mass.

As we break bread the light we pass

from face to face is Christ and incarnation.

Yet we do not share the feast with cedars

in the nave or squirrels who even now

in winter run upon the roof.

Seeking the focus of supernal action

as dancers move within the absolute,

the one beginning waits

in silence in a darkened sacristy

always preparing to enter like

a shadow, like the power of the child

in memory revealing, not a liturgy

unsaid, but seas and snowfields, places

we once played, crushed mulberries on sidewalks

the porcupine we startled in the wood.

To find the seedbed of events, you must

be empty of events. You have only to run

in silence with the eland.

On Christmas Eve

nothing is yet actual.

The created world

sleeps with the child

newborn, a gift in time.

We keep the feast.

As the choir invokes the Lamb of God

we are already lost, each circumstance

of giving a translation of beginning

into end. But on this Christmas Eve

just here, we walk dreaming down westward

aisles, beyond the end we know into a time

perhaps where gleemen sing, small and having

yellow eyes, and panthers breathe down cloisters

warm with cinnamon.

Just here perhaps and quite by chance,

purpled kings flash past us in the chaste and

given darkness, chaste as though we had kissed

before we knew that we must die.

[First published in A Christmas Pudding: A Yuletide Offering, 1986]

Streams of Mercy

?Weymouth Center, January 1978

Except a corn of wheat

fall into the ground and die,

it abideth alone.

Snow in the shrunken wood.

When it fairs off, as they say here

the season will turn cold.

For weeks now I have found

black husks of wasps in the old house

driven in by the chill—

heard their senile dives

at windows, thinking that winter

was something they never prepared for.

Mornings get the better of me now—

my debts forgiven might permit

that I should be alone in San Francisco

but it will not do.

I find the space I need

in the afternoon, to stir things up

before my blood burls down like sap

with the weight of other lives.

Beyond first fringes of trees

I jog around a little paddock

meet friends. We laugh

and shovel snow a while together—

then I go on. Life is heat, I think

gamy with becoming.

In the big meadow low clouds

continue my breath, Eros among

the ecologies, my body’s exhaust

connecting. Then down a long clay road

just covered with thin white dust

past pine and poplar smelling of oaksmoke

I run like an ostrich

fire under my arm.

I compose a letter to tell you

how I hear your voice

in winter silences

where aunts and uncles hide and seek

amongst old marriages.

Needing the child I was

I design a world in which

perhaps we sang Italian songs together

translated Rilke, whispered in the dark,

but my bubbling wrists (which now

especially do not touch your cheek) remind

me that winter gets into us all

turning our grave desires to gauds

that light our way as we perfect the past.

A boy crouches in early dusk

behind my eyes

knowing the center I seek

those to whom I have belonged,

belong. Certain years

ago I turned Episcopalian

studied Latin, failed at grief.

Today, my forty-year-old heart

beats at most one hundred eighty

beats per minute, give or take a few.

It slows a beat a year.

Now as our faces

recede into museums

my love tells over friends

and songs of Schubert, for whose sake

I once learned German.

I think that all our lives

are other lives, when leaving art I strive

to master transformations of my will

as I spent the summer of my nineteenth

year with Tolstoy, my thirtieth

with Middle English dialects. I have

gret wonder, be this light

how that I live—

A hand in mine fiercely grips my thumb.

Two shadow men we stand,

big and little.

Back in the meadow

walking now, I reach

for permafrost. I could stop

like Scott’s dogs on an instant—

click—like that, in mid stride,

my muscles blinked into crystals

my eyes unperceiving this long expanse

of winter, passionless

architectonic, the skin of the wasp.

I think I know his winter.

It is the distance between my hand

and yours, the given space we start from.

Summers we make ourselves, inside

our own winter skins.

[First published in Pembroke Magazine, 1981]

In Sure and Certain Hope

—I have been very jealous for the Lord.

I.

Lord,

I am unable

to expect a resurrection.

A good many absent

now call from overseas—

mostly I don’t answer.

I loved my grandfather as a slight man

of seventy, thin almost transparent

who whistled thinly through his teeth

as he sliced pecans with his pocket knife.

Once, before gum disease, heart attacks

and the flu pandemic of 1918, his teeth

had been his own. He stood six feet three

inches tall, my mother tells me, and weighed

two hundred pounds. Departed love does not

simply vanish but dies or lives according

to the mind’s experience—I almost said

according to whim. If there should be a resurrection

will I see my grandfather again and know him?

Will he be as I remember him

or the young man I never knew?

The question is naive I realize, but how

shall the dead be resurrected? St. Paul says

we shall be changed. Shall we have new bodies then—

and if so how is it that it is we

who shall be changed?

I loved my father, or rather, I loved

my father’s ghost. Dear heart, he wrote my mother

from a tent on Bataan, I set my microscope up

in the jungle today. We are trying to deal with sick call–

lots of malaria. In the citation from the war department

I read that he sacrificed himself for his weaker comrades

on the March to Manila, which he survived. In the newspaper stories

describing his life’s end (on a sinking ship torpedoed by his comrades)

I read how Japanese soldiers clubbed prisoners to death with rifle butts.

Oh hear us when we cry to thee—

I should pray for closure, but you did not ask

that I pray for such, only for daily bread.

A girl I grew up with, robust, rebellious

in the way West Texas gives beauty to some women

became my friend at college. Marriage broke her

before cancer. Not long before she died

she told me she had cut down

to ten cigarettes a day, her countenance innocent

as her morphine-drenched eyes. Suffering, having

refined the souls of many, might still be efficacious

but I am unable to expect a resurrection.

II.

Because we perish, we are immortal.

Yesterday I downloaded a photograph

of earth from space. The globe, familiar

from childhood as an object of faith

now sheathed in a thin wash of cloud, that breaks

here and there to reveal the outline of a continent,

floats in the small blackness of my computer screen—

a tolerable blackness, only a little like the silence

of eternal space that frightened Pascal. My less

than immortal soul recalls how the cello spoke

at Meyerson Symphony Hall, how fajitas tasted for

lunch. I should prefer to be resurrected than to prowl

the cycles of Karma with Oedipus, but the zest

of common life, the risk and the common loss

are as close as I can come to immortality.

I expect the predicted ice age to remain an inference

in my lifetime, expect that I shall perish before

my civilization and my family, but resurrection

generally seems not so much the final

cause of perishing as an empty falsification

—anger now is sharp and hard and timeless as a scythe.

St. Paul tells me that my corruptible must put on

incorruption, in the words of the king’s translators.

I think the order of being is otherwise: the incorrupt

corrupts, and nothing may be recalled. We know this

and deny the knowledge.

III.

A child stands at a window: looking

out or looking in, what is seen is secret.

Mynheers of Salisbury, recombinant DNA

peer through separate windows at the last secret.

Perhaps it is the secret of the Dutch countryside

straightened from the North Sea. Perhaps a bell

calls monks to prayer as forests of napalm

flower out to the strains of Mozart. Perhaps

the memory lapses into barbarism, a life taken

or death sought, pay the life price or not,

as Oedipus did—picture and memory drown among ships

cities in the Aegean lost like Noah’s flood

or the stories one can never remember at parties.

Somewhere between my father and grandfather,

what I have touched and loved and Oedipus shunned

is the common—the ayenbite of inwit not

conscience so much as a sometimes trivial

preoccupation with the details of the tragedy.

The ayenbite of inwit—

I compose two letters

to be placed in the same bottle.

You were often wrong, I tell my first

anonymous pen pal, especially when you

set it down that knowledge is easy, well begun.

You opened what you thought was the small

door to a small room, fairly well lit

and you thought you saw a domestic cat

sunning itself on a window seat. Perhaps

the tabby was there, but you missed the tiger

under the bed. On one wall you saw a clock

and on another a crucifix. You concluded

that all was well. Death was not in the

room at all, only a kind of death ex cathedra.

You were restless and you denied it, heartsick

for God and you denied that too. It was the clock

that comforted you.

An aggressive student argues passionately

that if Oedipus had acted reasonably

on the road to Thebes (i.e. refrained from killing

Laius, his father) he should thereby have avoided

the horror of his life. We agree that tragedy is the loss

of possibility, that freedom is tragedy the instant one acts

for the action closes off all possibility outside itself.

I maintain stubbornly that Oedipus acts according

to his nature, in which he is not given avoidance

that avoidance remains a possibility only in some

world that Oedipus does not inhabit.

Surely, I reason in my second letter,

you would not vouchsafe me the sharpness of thought

only to deceive my credulous nature. Surely some

grace transcends my particularity. Wisdom

(or perhaps Copernicus) teaches that the earth

roams restless in the empty firmament, but surely

some heaven obtains, not unlike the small blackness

of my computer screen, where speculum mentis

turns out a true cosmology, and the wished planet

turns home. The reply begins: Dear heart—

That which is somewhere possible could maybe be

a resurrected savior . . . .

IV.

Peace carries with it, says Whitehead,

a surpassing of personality—somewhere before

the tragedy starts, we learn the world, or rather

pose it to ourselves as a thing to be done

a set of occasions to be sought. A harmony

of harmonies attends the perishing

of that neurotic focus of attention

that was the occasion of our first being,

but desire for a second chance is the last infirmity.

Some inwit remains to the end, corrupts the child

one was, a sickness unto birth.

As I work now in this space before morning

I know that unspent grief draws interest, and that

is the real death. If I forego this unspeakable monody

who will forgive me, who will pay?

I compose a third letter, to a friend dead three days

into the new year. I tell him I loved his mind

even when it failed. For a while he had hoped

against hope for remission—he was my priest.

We said goodbye near the end, and for a brief time

I was his priest, too. I put my arms around him as I held

his sickness and my own.

[First published in Pembroke Magazine, 1997]

A sign at the park’s edge

warns me not to destroy or remove

any plant, rock, or mineral.

I wonder if water qualifies—

assuming a walk in the rain,

if I step in a puddle and carry

some water away, am I a thief?

I wonder if pine cones qualify, being

dead. I remove a few pine cones, strands of

longleaf straw, a few giant bull bay leaves,

parts of the local decay, as wormy webs catch

in my hair, wrap around my ears–all with a

watchful eye out for the ecology police. You never

know when some ardent urban survivalist will

round you up and strip search you, looking for

contraband pine cones in your bodily orifices.

Later, I walk in the big meadow.

Paths branch out like fringe from its edges,

connecting–every path joining another,

paths through, paths around, all going nowhere.

I meet persons on horseback who ask that I speak

so that their horses hear my voice.

They like that, the horses, they know then that I

am not a monster, that their masters need not

summon the ecology police. One master drives

a sulky, calls out a cordial hello

as he clucks his tongue to his trotter and murmurs,

“You’re all right, baby, you’re all right.”

Padding along I dream of secret houses

with mysterious inner rooms, entrances and exits

verging and merging but leading nowhere. The emotion

of my dream is a vague alarm, shot through

with occasional streaks of fear and a queer

joy. I think of Martin in his Black Forest hideout,

nursing bewilderment at the time that had so scarred

him and dreaming of numinous tropes. But why did even

he call language a house if not to evoke

some strife between nature and culture? The park sign

closes the woods off like a Texas cattle guard.

“Human, step no further!” it orders.

In the night a spider leaves its mark on my calf.

I am thinking of making a sign of my own: “Worms,

woods, insects, all other humanivorous beings, proceed

no further! Stay out of my bodily orifices. Make no new

ones in my skin. Announce yourselves by calling out

a clear hello.”

I step to the window to watch

the ecology police and see instead

scores of humanivores,

planting signs and fences

on pine cones, leaf mulch, ant hills—

“Harvester ants. Do not disturb!” one reads.

[First published in Pembroke Magazine, 2016]

Here in the knife shop

most folks don’t worry about the past.

August, and we are a good way out

the Jacksboro highway. The sun kills

anything that moves. Locked cars have been

known to explode.

Next door at the stonecutter’s, though

you hear a story worth a walk

through goatheads and broken glass

past the cur chained up in the daytime

who eyes you and growls down a row of blank

tombstones–he’s hit the end of the chain

too many times.

Behind the stonecutter’s shack

Robert E. Lee sits in a low chair

in the bed of a Model A pickup.

It was the present stonecutter’s

granddaddy, who carved him on order

from a town in Missouri, drove all

the way up there and had to bring him

back, because folks in Missouri wanted

Lee on a horse.

He’s still for sale.

[First published in New Texas, 1999]