On Memorial Day my morning ritual was accompanied by occasional bursts of patriotic music from the bedroom next door where my beloved was watching the morning news. She likes to watch TV in bed as she reads the morning paper. I drink coffee in the adjoining study in front of my computer and read the news on line, but at one point I went into the bedroom to watch as Vice President Biden presided over the familiar wreath-laying at Arlington Cemetery. I thought how, as a summer exercise, Americans of many political persuasions still allow one another the benefit of the doubt on the two three-day weekends that frame the month of June.

And about allowing one another the benefit of the doubt, I hoped it remains true–that in our increasingly tribal society we have ways of practicing our citizenship that transcend our differences. I used to think the 1976 bicentennial celebration allowed us to do that in the aftermath of the terrible divisions over the war in Viet Nam. Now I’m not so sure—about that and a good many other things. In the past couple of days I have attended two events celebrating Memorial Day. Both events demanded my participation in the rhetoric of American exceptionalism. Both events shoved Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the USA” in my face.

In the evening on Memorial Day, we watched Milk at my house. As that fine film reminds, the historical context of Harvey Milk’s death also includes the depredations of Anita Bryant. Bryant is still politically active, more’s the pity; though she seems to have fallen on bad times. A former website advertising her Oklahoma ministry is empty, and her MySpace page seems a rearguard action. It’s easy to see that Harvey Milk’s America and Anita Bryant’s are incommensurable. To my mind that same dissonance pretty much limns the difference between the Obama movement’s America and the Tea Party America of today.

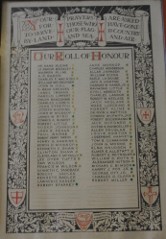

And speaking of rearguard actions, Sunday after church some of us gathered around a memorial to parishioners who had served in World War II. One of our fellow parishioners had found it in the church archives. A simple glass picture frame containing a handsome, hand-lettered sheet of paper listing sixty-nine names, most marked with stickers—mostly gold, though some are are stars and some not (we couldn’t figure out the color code). This memorial no longer hangs in my church, though I think it should, even though there is now no one among us who remembers any of the people listed. I note, too, that not all those listed are men. We will likely find a place to hang it again, and the antiquarians among us can perhaps discover who the people were. Maybe somebody will also discover why honour is given the British spelling. But why was this memorial plaque removed from whatever place it had in the church and placed in the archives? What was the thinking that led to its removal? As time obliterates memory, do memorials become curios?

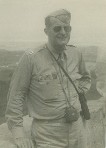

When I first started this blog, I wrote something about my father, who died in World War II. I’ve always liked this picture of him, taken at Ft. Bliss during training exercises before he and his comrades in the New Mexico Militia were sent to the Philippines as the United States 200th Coast Artillery in August 1941. He was a physician and a volunteer—at the time his unit was federalized physicians couldn’t be drafted—though he didn’t want to go overseas and hoped for a long time that the unit would be reprieved. I’ve always thought service in the National Guard was part of a payback for help with medical school—my father graduated from medical school in 1932—though I’ve never confirmed my suspicion. We saw him off with his unit on the train at El Paso a couple of days after my birthday that summer of 1941. He told me to take care of my mother. Here’s a bit more of what I wrote back then, paraphrased a little.

“More recently, I’ve read many of his letters to my mother. They describe his westward journey, first by train and then by ship, to the east, his arrival, much experience in the first heady weeks of his encounter with the MacArthur establishment. He didn’t like MacArthur, but I think he loved the old brown shoe army and relished being even a very lowly Captain, as he puts it in one letter, in that foreign outpost which must have had a certain old fashioned clubbiness and esprit. Then, of course, things turned sour. The letters are fewer from mid October on, and stop altogether in late November. One letter arrived after Pearl Harbor, written from a tent on Bataan in February, 1942. He died in 1944, somewhere in the South Pacific on an unmarked prisoner ship that was torpedoed by the U. S. Navy. The story of the sinking made the papers back home, with tales of escaping prisoners being beaten to death by Japanese marines. Of course that wasn’t anywhere near the whole horror of it.

“I learned more about the Japanese death ships when I read Dorothy Cave’s Beyond Courage a few years back. Apparently the Japanese used prisoner ships, marked with a red cross, to ship munitions, but there seems also to have been an intention to exterminate prisoners by transporting them on unmarked ships. Cave’s book also confirmed my impression from family and other history that my father and his comrades had been abandoned by their government when it was decided that the war in Europe took precedence over the far east. I learned too that my mother had been a member of an advocacy group during the war, that attempted to pressure congress and the president to rescue the folk in the Philippines. I found a collection of newsletters among her effects after her death. I also found a check for $100 that my father wrote to someone with a Filipino name. It was presented to my mother for payment after the war. The letter that accompanied it explained that my father had written it for black market medical supplies that he managed to smuggle into the prison at Camp O’Donnell.

“After his death was confirmed, they promoted him to Major and gave him some medals. One was a Bronze Star, the highest military decoration awarded to noncombatants. He also received a Presidential Citation, signed by Franklin Roosevelt, which my mother always cherished. I didn’t know much of this as a child. I thought my father’s Purple Heart more important than the Bronze Star, bigger and more imposing. And for a long time I refused to believe he was dead. I fantasized that he would come around the corner of my school one day and grab me up in his arms.” There’s an error in the Bronze Star citation. It dates my father’s internment from April 1941 and should read April 1942.

My father’s regiment was sent to the Philippines because its personnel spoke Spanish. It was a multicultural unit that included native Americans as well as hispanics and anglos like my father. It had been a horse cavalry unit only recently. I remember a closet full of my father’s cavalry uniforms and riding boots. It’s a nice irony that less than fifty years after the close of the Indian and range wars, and in a place where both had been pretty fierce, there was a military regiment that included soldiers whose recent ancestors had likely fought each other over territorial and other claims, some of them genocidal, now a unit engaged in a common struggle far from home and united in part by a common language that wasn’t English.