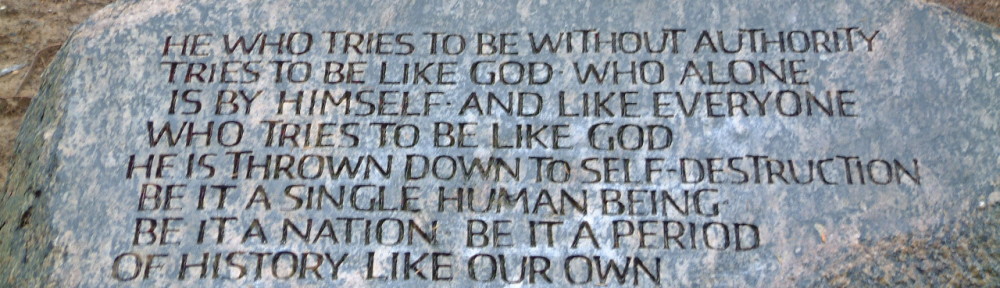

Paul Tillich is buried in a small grove of trees in New Harmony, Indiana. The grove is called Paul Tillich Park, and it sits just across the street from Phillip Johnson’s Roofless Church. Tillich helped to plan the site which, like the Roofless Church, was a project of philanthropist, Jane Owen. Owen had been Tillich’s student—the restoration and enhancement of New Harmony were her life’s work. I took the photo at the head of this essay about ten years ago in Paul Tillich Park. It is one of several of his sayings the philosopher/theologian chose to be displayed there along with this bust. Jane Owen died recently, but I like to think her work goes on as her legacy, and Tillich’s, continue in New Harmony.

I told my class last week that being in sight of eighty years I’m delighted that I have no idea when my own life will end. I am also very fortunate: to be in good health, and to come from a family inclined to longevity. Still, aside from the usual caveats faced by people my age, particularly the warnings my body periodically sends me not to take it for granted, I’m aware of being at a real juncture, a place that seems to require a pause not so much to take stock as to take new breath.

I’m suffering from something like information overload this year, though it isn’t exactly that. It’s more like Mrs. Moore’s muddledom in E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, in which history, temperament, old age, political consciousness, metaphysical uncertainty, all seem to conspire to to suggest a profound anomaly, to wit: the world has changed unalterably and become unrecognizable; and simultaneously, the world hardly ever changes—it is I who have changed.

She had come to that state where the horror of the universe and its smallness are both visible at the same time—the twilight of the double vision in which so many elderly people are involved. If this world is not to our taste, well, at all events, there is Heaven, Hell, Annihilation—one or other of those large things, that huge scenic background of stars, fires, blue or black air. All heroic endeavour, and all that is known as art, assumes that there is such a background, just as all practical endeavour, when the world is to our taste, assumes that the world is all. But in the twilight of the double vision, a spiritual muddledom is set up for which no high-sounding words can be found; we can neither act nor refrain from action, we can neither ignore nor respect Infinity.

My condition isn’t hopeless, as I think Forster thought Mrs. Moore’s condition to be, but it places before me a complex of questions, drops them on my plate like Proufrock’s works and days of hands. What may yet be done? What may it still be possible to think? How shall I bear myself towards a world that more and more seems to be characterized by irreconcilable disputes and wrongs without remedy? And somewhat less urgently, though equally relevant to my present condition, how shall I bear myself towards the prospect of my own unbeing?

I am an intuitive person. My thinking life—note that I don’t say intellectual life; that’s something else—has proceeded by fits and starts. I am seldom aware of the major movements of my mind until they are well begun. I approach them in medias res. I am, moreover, a literary person. What I know of what has been thought and said in my language, and to some lesser extent in a few other languages, opens resonant spaces in my thinking, supplies me with the fundamental categories of what I have learned from Richard Rorty to call my final vocabulary, though perhaps not all of its categories. As a result, thinking is for me an exploration and a sounding of those resonant spaces in hopeful anticipation of occasional release into more nearly original utterance. Original to myself, of course; I long ago understood that I arrive at new places in my thinking only to realize that others have been there before me. I cherish the hope as well that my literariness is not mere pedantry or belleletrism; albeit, it is so much a part of my nature that I can hardly hope to escape it.

Back to Mrs. Moore, whose untimely death occurs as an anti-resolution of the primary conflict of Forster’s novel. The muddle that does her in contains elements that resemble some of the dilemmas of postmodern times. She is a woman with advanced ideas, able to befriend Dr. Aziz, the novel’s Muslim Indian protagonist, resistant to the bigotry of other British characters for whom the Raj is a projection of the falsehood of Anglo superiority. She is also religiously unprejudiced, able to find God in the mosque where she first meets Aziz. Her own Passage to India, the combination of culture shock (symbolized by the echo in the Marabar caves), old age, the loss and grief contingent upon various personal betrayals, and perhaps simple exhaustion, proves too much for her, overcomes what might have been a heroic spirit. Before her death she is unable to help Aziz in his trouble, though she is certain of his innocence, perhaps partly because it is her friend, Adela Quested, who has accused Aziz of sexual assault.

Like Mrs. Moore I’m unable to defeat my own muddledom or to rise above it. In fact I don’t wish to do either thing. Neither religion nor ideology nor my social grounding offers me meaningful triumph, consolation, or even escape. But unlike Mrs. Moore I am unwilling (and I stress that word) to drift away into a fog of anomie. What I seek is to find the center of my muddle and to take up a position there. Like Wendell Berry I believe that the center is a position rather than an abdication. What I have begun in this essay, and will continue to do in subsequent essays, is attempt to address some matters that are contingent upon my having taken it up as well as being immanent in my thinking life and in my memories. As Montaigne wrote, “To philosophize is to learn to die”; or to paraphrase Berry in a different context, I seek to prepare myself for a world in which I will be dead, but not to avoid living as meaningfully as I am able all the way out to the end of whatever there is.

We’ve not visited New Harmony, Indiana, since 2008. At that time some favorite places were gone, notably the Golden Raintree Bookstore, where we had spent a good many happy hours and where I once found a beautiful copy of Drums, by James Boyd. The town’s remarkable public library remains, though. Denominated the Working Men’s Institute, it serves as the town’s chief reminder of New Harmony’s brief ownership by Scottish industialist Robert Owen, of a past grounded in Utopian idealism and the earliest stages of the international labor movement.

New Harmony—from Paul Tillich Park, a monument to the most privileged and elite European education in the person of one of the finest products of the prewar German university system, to the Working Men’s Institute, a forceful reminder of the ideal of universal education, of the joining of practical learning with the impulse to philosophy in the broadest sense. And the two just a brisk walk from one another.

Hints and nudges toward finding the center of muddledom.

John J. Audubon’s Birds of America.

“Our schooner now sailed onward, and carried us to the dreary shores of Labrador. There, after some search, we met with a great flock of Arctic Terns breeding on a small island slightly elevated above the sea. Myriads of these birds were there sitting on their eggs. The individuals were older than those which we had seen on the Magdalene Islands; for the more advanced in life the individuals of any species are, the more anxious are they to reproduce, the sooner do they proceed to their summer residence, and the more extensive is the range of their migration northward. On the other hand, the younger the bird is, the farther south it removes during winter, both because it thus enjoys a milder climate, and requires less exertion in procuring its food; whereas the older individuals not only have a stronger constitution, but are more expert in discovering and securing their prey, so that it is not necessary for them to extend their journey so far.â€

http://tinyurl.com/nu3j9q8

Curtis, Duke Library owns one of the 120 complete sets of Birds of America. It was displayed in the rare book room and a page was turned over each month at the time I was there, so I’ve seen a good many of the plates. Right now, the volumes are in storage as the rare book room is being renovated, but I’m sure the open display and page turning ritual will continue when the room reopens this summer.