The title of my last ramble was taken from a sixteenth century poem by the Englishman, John Davies. “Nosce Teipsum,” know thyself, interestingly, is misspelled at the Poetry Foundation website, here. I used Davies’ spelling, itself perhaps a variant of the popular aphorism nosce te ipsum, because my general subject was Christian humanism. Davies (1569–1626) was a courtier and a lawyer, not a professional poet. Almost all his poetry belongs to the early part of his life, before he bacame embroiled in public affairs. He sought and gained the favor of Queen Elizabeth, who appointed him to various public offices. After the Queen’s death he served among the delegation that brought James VI of Scotland to England to be king.

“Nosce Teipsum” is a long philosophical poem that is sometimes regarded as a compendium of Elizabethan knowledge. It is hardly that, but it is a profoundly conventional poem, essayistic, of that species of sixteenth century English poetry that C. S. Lewis called drab. It has two claims to fame, its early use of the decasyllabic quatrain (which Davies didn’t invent) a verse form sometimes known as the elegaic measure because of Gray’s later use of it in his famous elegy. But Davies’ poem is better known for the three quatrains that conclude its first section, subtitled “Of Humane Knowledge”:

I know my bodi’s of so fraile a kind,

As force without, feauers within can kill;

I know the heauenly nature of my minde,

But tis corrupted both in wit and will:

I know my Soule hath power to know all things,

Yet is she blinde and ignorant in all;

I know I am one of Nature’s little kings,

Yet to the least and vilest things am thrall.

I know my life’s a paine and but a span,

I know my Sense is mockt with euery thing:

And to conclude, I know myself a Man,

Which is a proud, and yet a wretched thing.

Immediately prior to these stanzas, the poet avers: “My selfe am Center of my circling thought, / Only my selfe I studie, learne, and know,” in lines that suggest an acquaintance with Montaigne. But by 1599, the year of the publication of “Nosce Teipsum,” this idea, like the sentiments that follow it in the poem, was part of the conventional conception of Human nature about which philosophers from Descartes to Locke and Berkeley mused. A later, and better known, example is Pope’s aphorism:

Know then thyself, presume not God to scan;

The proper study of mankind is man.

My point is not to argue for the correctness or the venerability of the caveat, though Davies invokes Socrates as an originator. I mean rather to allude to Davies’ poem as a typical product of Christian humanism in his time, not so beautiful or monumental as the 1559 Book of Common Prayer or the English Bible (KJV 1611) or so influential and original as the Institutes of John Calvin (1536), but perhaps more typical because more ordinary. In the first section of the poem Davies’ theme is the limits of human knowledge; in the second, the immortality of the soul. In both sections he draws upon a variety of classical and biblical sources in a manner thoroughly commonplace in his time.

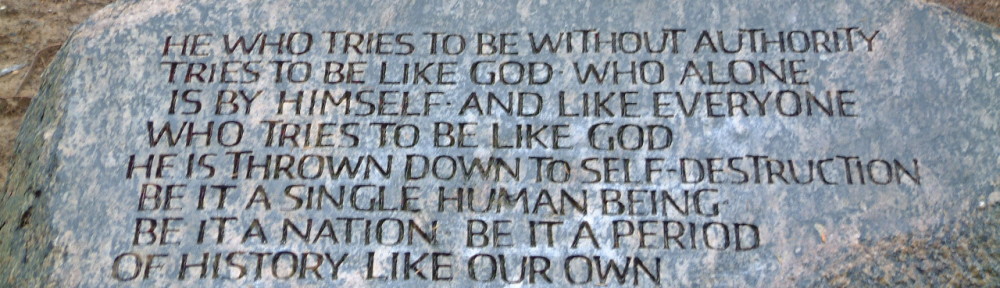

The stone whose photograph I have used at the head of this post and the last may be found in a small garden in New Harmony, Indiana that contains the grave of Paul Tillich. I have referenced it once before, here, and noted its proximity to the Roofless Church, designed by Phillip Johnson.

Sidney’s reference to Anchises calls up a moment in Virgil’s Aeneid after all is lost and the city has been destroyed. Aeneas escapes carrying his father, Anchises on his back and leading his son, Ascanius, by the hand. His wife, Creusa, is unable to keep up with them and falls behind. When Aeneas searches for her after satisfying himself that his father and son are safely hidden, he finds that she has been killed. There follows a tender conversation between the living Aeneas and Creusa’s ghost. (Aeneid, II, 705–795)