The carol is the creation of John Mason Neale, a noted anglo-catholic clergyman, champion of the Oxford Movement and author/translator of a good many familiar hymns, and Thomas Helmore, a musician who was Neale’s clerical colleague and collaborator in a number of plainsong collections and anthologies of carols. The tune of the Wenceslas carol is that of a traditional spring carol, “Tempus adest floridum.” The winter/spring juxtaposition has not pleased some modern critics, but the continued popularity of Neale’s carol has made his appropriation of the tune permanent.1 All of which is a wonderful exercise in living by fiction, not exactly what Annie Dillard meant by the phrase in her somewhat overthought book with that title, but indicative of the familiar process of mythopoeic appropriation as Mircea Eliade has treated it in a long series of books.2

One need not accept Eliade’s conception of the history of religions in order to understand that this process occurs and that it yields ahistorical texts which from time to time may be taken for history. And, lest the deconstruction of such texts be taken for a new thing, it might be pointed out that Thucydides read the Homeric poems as history, and Plato did not. Wikipedia’s article on the Duke of Bohemia attempts to historicize Wenceslaus and to present his death as part of a family feud, but here is another account of the life of Wenceslaus that entirely accepts the heroic legendary King. Yet ahistorical texts themselves have histories, and lest it be thought this point is the product of a postmodern awareness of textuality, it is nowhere clearer than in that moment in Quixote II when the Don confronts the “true” account of his adventures coming off the printing press in Barcelona, where he has been greeted as “valiant Don Quixote of La Mancha, not the false, the fictitious, the apocryphal, that recent days have offered us in lying histories Šbut the true, the legitimate, the real one that Cide Hamete Benengeli, the flower of historians, has described to us.”

Says Quixote of the printer’s version of him,

I have heard of this book already, . . .and verily and on my conscience I thought it had been by this time burned to ashes as useless . . . ; for fictions are better and more entertaining the more nearly they approach the truth or what looks like it; and true stories, the truer they are the better they are.

My beloved and I live less than a mile from Saint Wenceslaus Church in St. Louis. Ahistorical texts serve a variety of purposes; and the truer they are the better they are, surely.

Notes

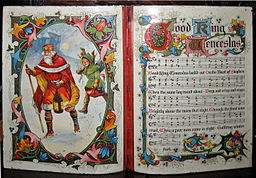

1The photo at the head of this post shows a 1913 biscuit tin, on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum. Credit for the photo may be found here.

2For Eliade’s classic treatment of this theme, see The Myth of the Eternal Return: Or, Cosmos and History, tr. Willard Trask (New York: Bollingen: 1954).