I had thought to return to talking about politics this year. The plight of the poor and the weak among us seems urgent to me, as does the plight of our infrastructure and of our treasury of cultural institutions in these hateful political times. But I have searched my soul and found that I’ve already said most of what I have to say about these things.

I’m also concerned that many in my my country seem determined to promulgate a false history to rising generations in a time when authentic memory of the terrors of slavery and the native American genocide are fading as the generations die. But no appeal to a more honestly usable past can save us from true believing folk who imagine that the cosmos is only about six thousand years old; and it doesn’t help that many of these people are good and dear, and that I love them.

I long ago resigned from these arguments. I may return to politics, but if any of my friends are still comforted by the belief that they will not meet me in heaven, I wish them comfort and decline to pursue that issue further. Besides, winter is dragging on. I don’t mind the cold and snow we’ve had recently, but lately we’re in the grip of the sort of indifferent, soggy, in-between weather that keeps one indoors in spite of warming temperatures. I don’t trust this weather any more than I trust my country’s politics.

Over last weekend we had balmy days. The cosmic world stayed the same in spite of the hour we lost as political and commercial spheres shifted to Daylight Saving Time. I’ll be glad for the light in the evening hours as spring and summer return and envelop us. I look forward to cooking outdoors again and to watching the summer fire flies from my back porch. But we’re not there yet, and I’m thinking we’re in for at least one more cold snap before the season advances. Of course I have no idea about this. Weather Underground is forecasting mild temperatures through the middle of the month, but the Farmer’s Almanac is less optimistic and suggests we may have one more snow before April. As I’ve said more than once before in these pages, I’m feeling the pull of the cosmic cycle more and more every year, every season. Perhaps I take this indifferent weather, if not as a portent, at least as a memento mori. One of the home truths of my time of life is that every so often it dawns on me that I’m not immortal.

I hesitate to talk about intimations of mortality for fear that people I love will rush to my side to comfort me or otherwise persuade me to stop being morbid. I don’t feel old, but I know that at two years shy of eighty I am almost as old as dirt; and I know I need a strategy for dealing with the remainder of my life. I don’t mean to call up the usual bureaucratic end-of-life specters. I have a living will and a regular will and a caring spouse who has my power of attorney and children who love me. I have no fear of being subjected to mechanistic horrors as I leave the world.

But I need a strategy for living in the shadow of death in a new way, because my own death is closer to me now. Not that I am suffocated by the thought of it or overwhelmed by fear. My need is rather an inner need that reflects my awareness of that part of myself that corresponds to the real world into which we are born and in which we love and hate and into which we bring our children and through whose environs we struggle with ourselves and others and search for happiness and fulfillment and goodness and meaning and God, a world more real to me now than its symbols and rituals. I stress that I am not looking for pie in the sky. But I am indeed looking for something that isn’t exactly cultural, though it certainly has a cultural dimension.

I’ve been reading Jacob Needleman’s Money and the Meaning of Life. After I was ill last summer I re-read his Way of the Physician. I had first read it years ago as a possible subject for a Dallas Morning News Book review. I didn’t review it and now don’t remember why, but Needleman’s willingness to face up to basic questions of life and death without resorting to conventional pieties, particularly bureaucratic pieties, drew me to him. This new book (new to me; it was published in 1994) argues that we should take money more seriously than we do, since it is the chief organizing engine of our worldly life.

Quite so: though Needleman’s real project is to persuade us that there is a higher life than the life of money that is only accessible after we have paid our debt to Caesar. I am drawn to this view, though not to Needleman’s theosophy or his interest in Gurdjieff. Nor do I necessarily think the other life, the not-money life, is higher. I think it is other. I think it is the pearl of great price. I agree that the obsession with money blinds us to it, blinds both rich and poor. Access to the not-money life requires, I believe, the fact as well as the understanding that one has enough.

It may require other things as well. It may require particularly the realization that one’s own good is intertwined with and dependent upon the good of others, perhaps the good of all. And not merely the good of all humans, but perhaps the good of all creatures great and small, as that lovely hymn sings to us. It may require an ethic such as that we are attempting to envision in present-day conversations about sustainability.

Sustainability is not a new idea, but it rests upon a vision of community that has never seemed attainable within the framework of modern capitalistic conceptions of the world. Sustainability orders the world according to need; capitalism, according to desire. Sustainability might ultimately conceive the withering away of money as shared wealth took the place of individualistic acquisitiveness and avarice.

But my purpose isn’t to propose a Utopia, either as a social goal or as a satiric heuristic. My point is to suggest a need in myself for a new framing of the ancient ideal of seeking the Kingdom of God. The love of money yields as abstract a life as any degenerate monasticism. The Kingdom of God is existential, here and now if it is anywhere. So far, the most telling evocation of the Kingdom of God for me is Wendell Berry’s essay, “Two Economies.”

We know from our own experience that it is possible to live in the present in such a way as to diminish the future practically as well as spiritually. By laying up “much goods†in the present—and, in the process, using up such goods as topsoil, fossil fuel, and fossil water—we incur a debt to the future that we cannot repay. That is, we diminish the future by deeds that we call “use†but that the future will call “theft.†We may say, then, that we seek the Kingdom of God, in part, by our economic behavior, and we fail to find it if that behavior is wrong.

I think we may have reached a point in the history of life on this planet when something like sustainability may be forced upon us by our own excesses. Our cities are rotting, no matter what their chambers of commerce say. I will not live to see it, but we shall soon, as a people, begin to experience a loss of habitat similar to that we have visited upon our planet’s non-human creatures—as oceans rise and the planet’s surface becomes less habitable.

Cities have never been sustainable. Our present-day landfills are but the latest iteration of the refuse heaps by which cities have been known for centuries. Perhaps this is one reason why the dream of community tends to be agrarian, as it is with Berry. Nor is there any sense of a sustainable human community in the Utopias of the past; though perhaps the Eucharist and similar ritual meals symbolize the aspiration towards such a thing. Tim Burke has two excellent discussions on his blog right now of what it might mean to think of sustainability in terms of the needs of modern urban societies and bureaucracies. He concludes that it’s hard to imagine what such a thing might look like.

So here I am, an aging man living in an old house whose builders had no idea of me, in the midst of a city that had no idea of me in the past and has precious little idea of me now. If I followed the normal path many Americans my age follow I would discard my house and move to a “retirement” community soon. At some point I will likely be forced to make that move as my ability to manage my small economy (see Berry) declines, as I become less and less able to climb stairs, for instance. The question of sustainability for me is now less a question of trying to imagine the future of my city at large than of forming and maintaining a particular intentionality as I regard the prospect of my city’s departure from me personally.

I’m not planning to let go gently, and as I think about staying in my house as long as I can my cosmic life and my abstract life coincide. I could wish, with St. Paul, for a continuing city to come, but I don’t. The prospect of an eternity of consciousness in an unchanging place isn’t attractive to me. And at this point I realize what my thinking has left out. I have loved my life, loved places, loved the sheer presence of mountain and ocean and prairie, loved seasons and tides and the sun and moon. St. Francis praised these things as his brothers and sisters. But I have loved my city too, some manifestations more than others. In Denton it will always be sunset in McKenna Park and I will always be pushing my little son in the swing there as we look across the prairie towards Decatur.

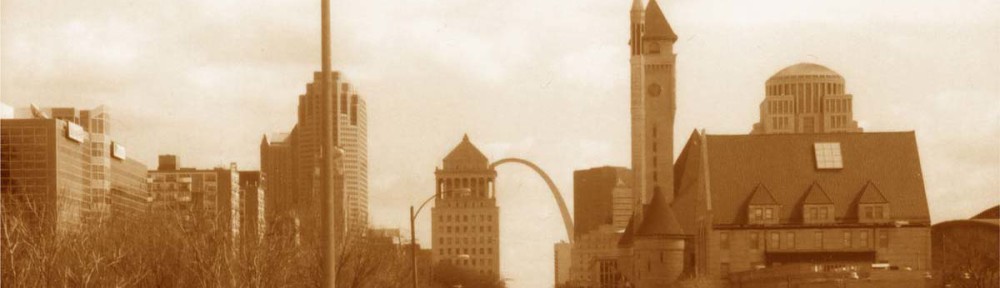

In Dallas it will always be the end of an evening when Giles Mitchell and I walked along Snider Plaza trying to dance like Anthony Quinn, having just seen Zorba the Greek at the Fine Arts theatre. In Raleigh I will always be jaywalking with Shelby Stephenson in search of the Executive Mansion the night Sam Ragan was awarded the North Carolina Medal. I shook Jim Hunt’s hand that night, but laughing with my friend as we got lost (or didn’t) meant more. And here in this old city whose river is a strong, brown god, and where I have fallen in love with life and my beloved all over again, I think I am a citizen of no mean place, to borrow from St. Paul another time. Even hollowed out and given over to corruption of every kind Saint Louis is a consummately human place, rich with the sorrows and laughter of many languages. It will certainly outlast me.

And the Kingdom of God? It contains the ten thousand things and the joys and terrors of them partly because it is full of death. It is the awareness of death around me that provides me with the conscious will to live; and it is the knowledge that my life is finite that makes it a life at all. This is a real knowledge to be distinguished from the forms of abstract knowledge that have occupied most of my attention all these many years. For the truth about the cosmos and me is that I shall finally be abandoned, or recycled, as the cosmic stream moves on. My city, like my life, struggles against abandonment. In the end the only real issue is how to lose—and so I think again of Cavafy’s poem:

As one long prepared, and graced with courage,

as is right for you who proved worthy of this kind of city,

go firmly to the window

and listen with deep emotion, but not

with the whining, the pleas of a coward;

listen—your final delectation—to the voices,

to the exquisite music of that strange procession, . . .